When the “Different” Learner Meets Cursive

by Kate Gladstone, author of READ CURSIVE FAST

Most folks today don’t write in cursive. Some people never even pick up a pen or pencil. Writing in cursive has become rare — yet reading cursive remains an important life skill, whenever:

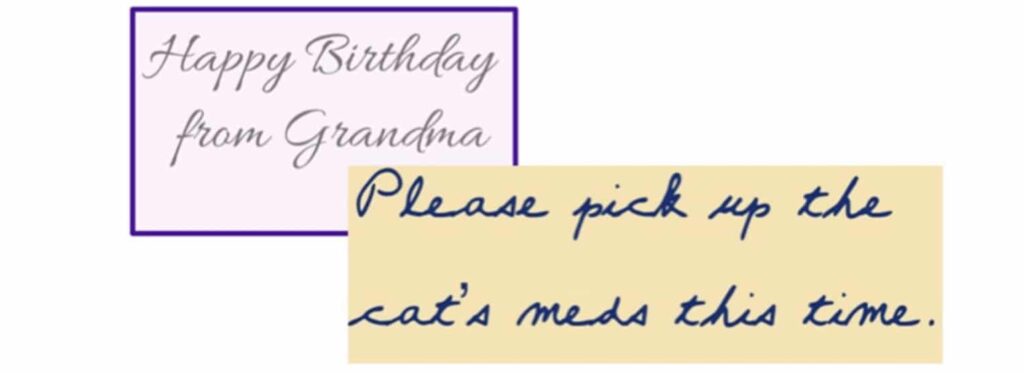

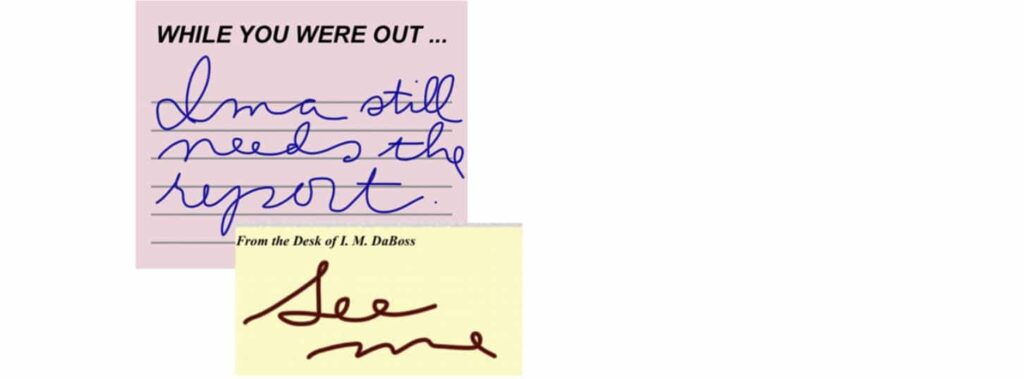

- family members still use cursive, or even send greeting cards that use cursive fonts:

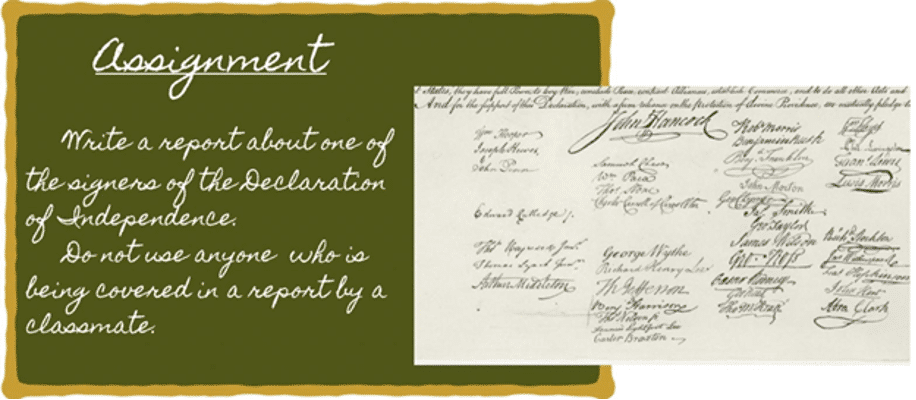

- teachers use cursive, or assign work that involves reading historical documents in their original form:

- employers, supervisors, or co-workers use cursive:

- store signs or logos use cursive:

Today, more and more children and adults — with and without disabilities — cannot read cursive handwriting, or can only partially and laboriously figure out a word or sentence in cursive, even if the cursive writing is clear and error-free (which is often not the case). These difficulties occur at all educational and socioeconomic levels.

In the USA, Canada, India, and many other countries, non-readers of cursive include most people 35 and under, as well as a surprising number of older adults who have often managed to hide this problem throughout life.

Worse yet, today’s millions of “cursive non-readers” (with or without disabilities) aren’t limited to those who were simply never taught cursive.

Even when conventional cursive training actually does lead to reading (and writing) cursive, those “successful” learners often lose the ability sometime between the year that they are taught cursive (typically Grade 2 or 3) and the year that they leave high school.

This situation was profiled in 2013 by one of Canada’s largest newspapers. The cursive non-readers whom that article were college freshmen. By now, almost eight years later, they must be in their mid-twenties: they have jobs, or are trying to get jobs, and probably some of them have families. (How will cursive non-readers help their children, if the school or the district or other administration mandates cursive instruction?)

Forgetting how to decipher cursive (or never learning how to decipher it in the first place) can happen anyone — but it more severely impacts people with dyslexia, autism, and other neurological differences that affect how we perceive and process the data that our senses provide.

People with various neurological differences (autism, dyslexia, dysgraphia, and more) are often very good at looking for patterns — and are extremely good at seeing patterns in the surrounding environment, without ever even having to look for the patterns! The patterns, especially visual patterns, simply jump out as them — or, I should say, simply jump out at us (because I have several of these “dys-”abilities). Therefore, we use visual patterns to try to make sense of what we are trying to learn — and we learn best when we are encouraged to use visual patterns.

However, students who encounter cursive are often discouraged from even trying to wonder if there are visual relations between the cursive letters and their printed counterparts. The two systems of writing, appear unrelated to each other:

Since it looks as if there is no relationship between most cursive letters and their printed counterparts, many learners frustratedly give up on even trying to use their visual/pattern-recognition strengths to “crack the code” of cursive. When the visual/pattern-recognition strengths of a learner’s brain are suddenly made useless, he or she may feel that his/her brain has stopped working and can no longer be trusted. (Such a learner may be said to have “form constancy issues.”)

Unfortunately, well-meaning parents and schoolteachers may accidentally push learners even further in that direction, by trying to reassure frustrated learners of cursive that “there is really no relationship between cursive and printing anyway, so don’t even bother trying to see a relationship or a reason or an explanation. Don’t even think that there could be a relationship between one style of letter and another. There is no relationship, nothing to find, is nothing to understand, so just memorize, don’t worry, and you’ll pick it up just fine, I’m sure.”

However, “just memorizing” (without understanding) is an extremely fragile and worrisome way of trying to learn and remember. What is memorized without comprehension is quickly forgotten, as soon as lessons are over — Especially in modern times, when fewer and fewer people write cursive (or even write by hand at all) in life after school the liabilities of “just memorizing” hold true for most people, to some degree — but they almost always hold true, to a huge degree, for people whose neurology differs significantly from the average.

When learners are told that “there is no reason, only memorization,” and when they experience no way of fully understanding the material that they must memorize , they lose trust in their own ability to even try to learn and understand: at a basic rote-memory level, and/or at any other level.

This is especially true when the subject is cursive handwriting , because — for many students learning cursive — the cursive textbook is typically the only textbook that is full of assigned material which they cannot read (although it is in their own language) but must still copy.

One part of the visual skills/form constancy problem is that the shapes of cursive letters are often inconsistent from word to word, in ways that can make words very hard to recognize.

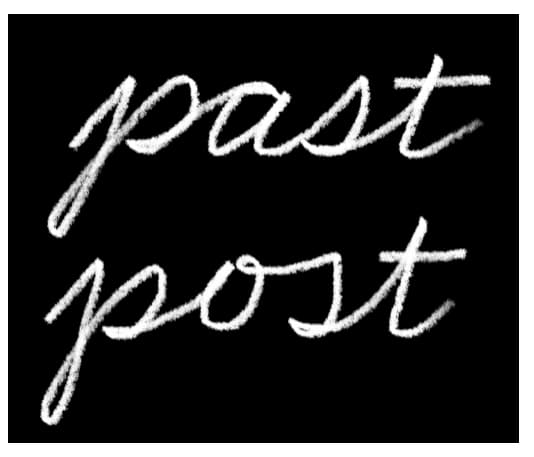

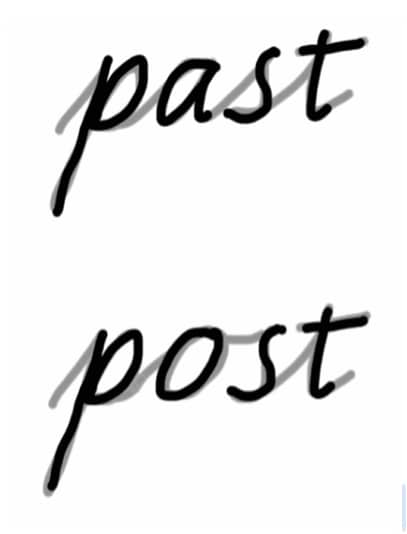

Look at these cursive words:

In both words, the third letter is a cursive s — but the “same” cursive s is very different each time:

A learner who has memorized the cursive s in past (where it needs to start at the bottom) is likely not to recognize the “same” cursive s in post (where it needs to start at the top):

For any learner — but especially for one whose neurology is not the “average” that textbook publishers assume — all this can deeply shatter confidence and motivation.

Does it have to be this way?

Can we make cursive make sense to all learners — even if they don’t write cursive, or if they don’t write by hand at all?

What if we showed our learners how cursive happened?

A new book, READ CURSIVE FAST (National Autism Resources, 2021), takes this approach: offering three easy stages to lasting cognitive comprehension (not just fragile rote memorization) of what makes a cursive letter a G or a Z or an r or an s — and why. Now, learners’ visual strengths, pattern-recognition strengths, and cognitive strengths can work in synchrony instead of being neglected or frustrated,

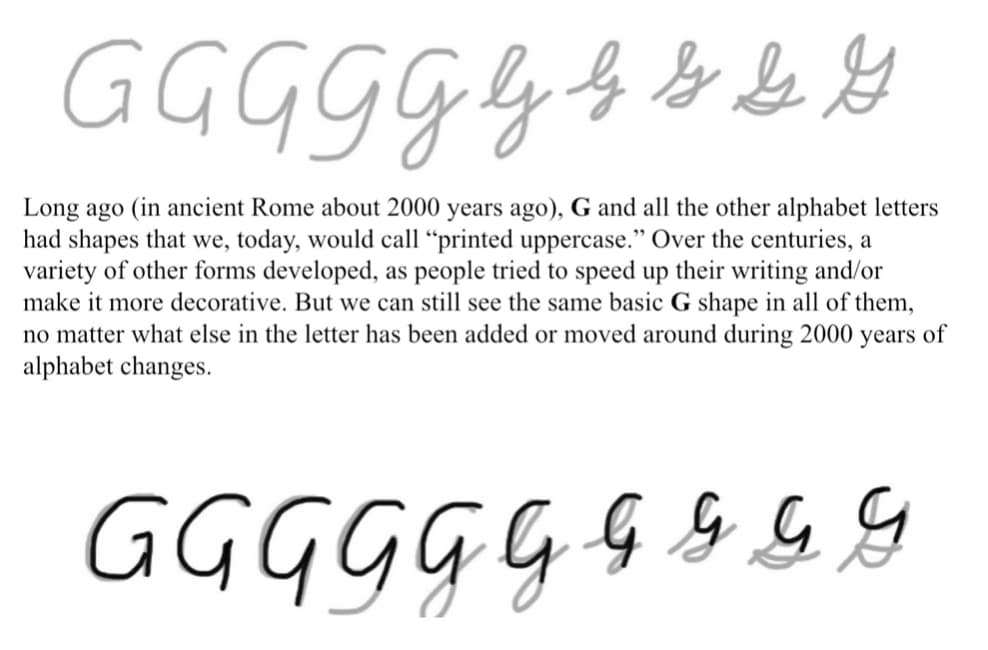

Step One: Show how cursive letters happened!

When readers are allowed and encouraged to learn how cursive letters came about, remembering the cursive shapes makes cognitive/pattern-recognition sense, and does not have to rely solely on rote memory. Here’s an example for the letter G:

READ CURSIVE FAST uses a pattern-recognition/cognitive approach to “unlock” the visuals of every cursive letter. Some letters need to be cracked in step-by-step detail, while others can be “cracked” more simply:

When you see the print-style s hiding inside cursive s, you can see why the cursive s looks different after lowercase o versus the way it looks after lowercase a.

Building pattern recognition and understanding into the learning task makes for faster progress and greater retention, by providing another route to comprehension. Cursive writing is not the only path to cursive reading — for many students, it is not even a reliable path.

Step Two: Sustained Reading

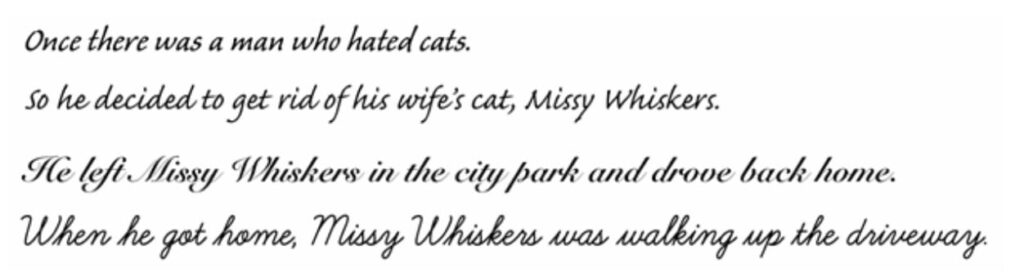

Once students recognize cursive letters alone and in words and phrases, it’s time to build automaticity and fluency with longer texts. To accomplish this, READ CURSIVE FAST uses “cursive stories”: passages written in fonts that resemble increasingly difficult styles of handwriting. Here is the opening of one story:

___________________________________________

(The first four sentences of a cursive story from READ CURSIVE FAST.)

___________________________________________

The beginning of each story resembles familiar printed letters, but each sentence adds more and more cursive features, carefully easing readers into understanding increasingly complex forms of cursive.

Step Three: Reading Historical Documents

Once students can read present-day cursive with some fluency, they will eventually want or need to read our nation’s historical documents, many of which are written in very elaborate forms of cursive.

Today, reading historical documents is one of the most frequent reasons for needing to read cursive, but handwriting style variations in past centuries were even more frequent than they are today. This means that most students (particularly those with neurological issues) will benefit from practice with historical cursive samples once they are experienced in reading present-day cursive samples.

Therefore, READ CURSIVE FAST includes a section specifically on historical documents. Learners reach this point are usually pleased and amazed that they can now read historical material.

When we know how each cursive letter happened, we know (and we never forget) what makes the letter understandable. Whatever our own handwriting looks like, whatever style we use, or even if we never write by hand at all, we can make sense of every cursive letter we are shown what parts of a cursive letter make that letter make sense.

When cursive letters make sense, we do not need to write cursive in order to read it.

When we make sense of the interrelations of different alphabet styles — print and cursive and more — handwriting becomes …

As the author of READ CURSIVE FAST, I look forward to seeing and hearing your own experiences and thoughts on cursive reading issues.

The book’s web-site — ReadCursiveFast.com

Sample pages for free download — http://readcursivefast.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RCF_Preview-1.pdf

Link on the publisher’s site is here: https://nationalautismresources.com/read-cursive-fast/

Links to buy READ CURSIVE FAST directly from me: ReadCursiveFast.com/order and https://read-cursive-fast.myshopify.com/

Category: News